Decoding the Supreme Court

Last week, the Supreme Court decided DNA could not be patented. But some types of DNA were left fair game. The justices made errors and left it difficult to explain.

Last week, the Supreme Court delivered a lesson in biology.

Trouble is, it was a lesson that puzzled some trained scientists and left some science communicators quite unsure how to explain it.

The Supreme Court ruled on the case of Myriad Genetics, the biotech company that isolated two genes with mutations known to put women at high risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer. Myriad patented these gene sequences, called BRCA1 and BRCA2, and developed a test to screen women for them. Myriad controls the patent and thus, controls the availability the test.

Last week, the justices decided the following:

Myriad did not create or alter either the genetic information encoded in the BCRA1 and BCRA2 genes or the genetic structure of the DNA. It found an important and useful gene, but groundbreaking, innovative, or even brilliant discovery does not by itself satisfy [the conditions for patent eligibility].

In essence, while recognizing the complicated and time-and-money-intensive process required to identify and isolate genes for use in screening, the Supreme Court unanimously said Myriad should not be able to hold a patent on the genes.

It justified the decision on the grounds that Myriad did not create anything new. Because DNA – and these mutations – exist in nature and the genes isolated are exact replicas of the DNA in the body, Myriad’s sequence was not novel.

You cannot patent nature.

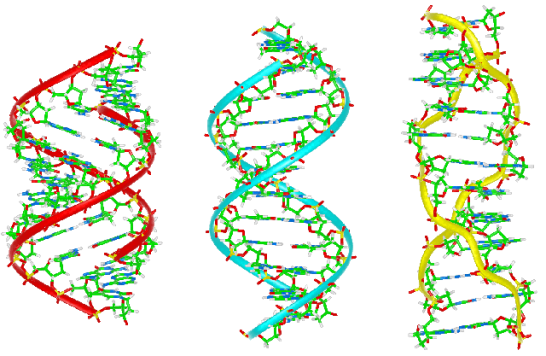

Now, the opinion published by SCOTUS is dense with descriptions of DNA, transcription and translation (the process of making a protein from DNA), DNA isolation and more. Someone did their homework, though the descriptions are complicated and heavy. Still, the science is mostly right. (Here are a few examples where their explaining goes awry).

While the opinion included some (almost philosophical) debate about whether breaking the bonds holding DNA together or isolating a segment of the DNA that normally would not exist on its own make what Myriad did patentable, in the end SCOTUS said no.

Nothing too puzzling here. That came later.

Further down in the opinion, the justices decided to tackle whether cDNA, or complementary DNA, can be patented, because of other patent claims held by Myriad.

Scientists use cDNA all the time because it allows them to more easily create proteins needed for studies as varied as exploring how viruses infect cells, how proteins interact with one another, or how to create gene therapy approaches for hereditary diseases.

As most of us have probably learned at one time or another, all of the genetic code that makes us, well, us, is contained in our DNA, located in the nucleus of our cells (except for sperm and egg cells, where it’s only half our DNA). This DNA is called genomic DNA and includes all the genetic stuff – genes – that tells our bodies to make proteins, which do the work of our cells. It also contains a massive amount of stuff that doesn’t get made into proteins.

Scientists used to call this “junk DNA,” though increasingly the idea that it’s useless has been rejected. This non-protein-coding stuff, called introns, makes up anywhere from 80-90 percent of our genomic DNA.

When the body goes about its business making proteins, the first step is to make a message from genomic DNA called messenger RNA, or mRNA. This message includes only the stuff needed to make a protein and none of the introns. Scientists can reverse the process using a natural enzyme to create DNA from the mRNA, but the DNA created doesn’t have any of the introns. Instead, it’s all coding stuff.

This is the cDNA. It is complementary to the mRNA.

Now this is where the Supreme Court decision got weird. The justices determined that because scientists in a lab have to synthesize the cDNA – meaning, they can’t find it hanging out in a cell or pull it out of a cell using a chemical process – cDNA is a “synthetic” product that can be patented.

Here is a passage from the opinion:

A naturally occurring DNA segment is a product of nature and not patent eligible merely because it has been isolated, but cDNA is patent eligible because it is not naturally occurring…cDNA is not a “product of nature.”

Howard Temin and David Baltimore may have turned over in their graves. These two scientists independently discovered the natural enzyme other scientists now use to create cDNA and they didn’t have to “synthesize” it. In fact, at the time it was discovered, it made waves of tsunami proportions because it challenged the long-held notion nature moved from genomic DNA to mRNA to protein and never in reverse – the so-called “central dogma.”

The enzyme is called reverse transcriptase and it’s what enables the HIV virus to multiply in human cells. The HIV virus stores its genetic information as RNA, not DNA. To make more of itself, it hijacks the machinery of human cells to make copies of its genetic material. It must first turn its RNA into DNA so the body doesn’t know it’s there. You know, the stuff that’s “complementary” to its RNA. It uses reverse transcriptase to do so.

The definition of cDNA as something that does not occur in nature is tenuous at best. Other viruses are capable of the same thing. And cDNA may exist elsewhere, too, but the research isn’t there yet. The link above, on the scientific inaccuracy of the justices’ opinion, explains pseudogenes and how cDNA fits into that story.

Last week’s decision was an interesting one for scientists and science writers. It’s not everyday the Supreme Court takes on something so deeply rooted in basic science. And their treatment reflected it (especially Justice Scalia’s judgement).

As scientists and communicators, our job is to help people understand the difference between the Supreme Court’s interpretation and what the science really says. Can we be effective?

For more reading on the specifics of the Supreme Court case or on Myriad’s path to patenting DNA, read this, this, this, or this.